Foods of Papua New Guinea

October 24, 2016

Although there's a distinct lack of Chicago-style pizza restaurants here in Ukarumpa, there's lots of other tasty tropical treats available. For example:

And, moving on from the produce department...

Scripture App Builder

October 16, 2016

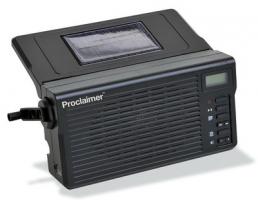

When the Bible is translated into another language, it is often made available to the speakers of the language in more forms than the printed word. One of the alternate formats that is most effective is the audio recording. Many cultures value the spoken word over the written word, and even in those that do not, an audio recording is able to be understood by everyone regardless of their level of literacy. Historically, audio Bibles were distributed on devices dedicated to the purpose, such as the Proclaimer or Audibible.

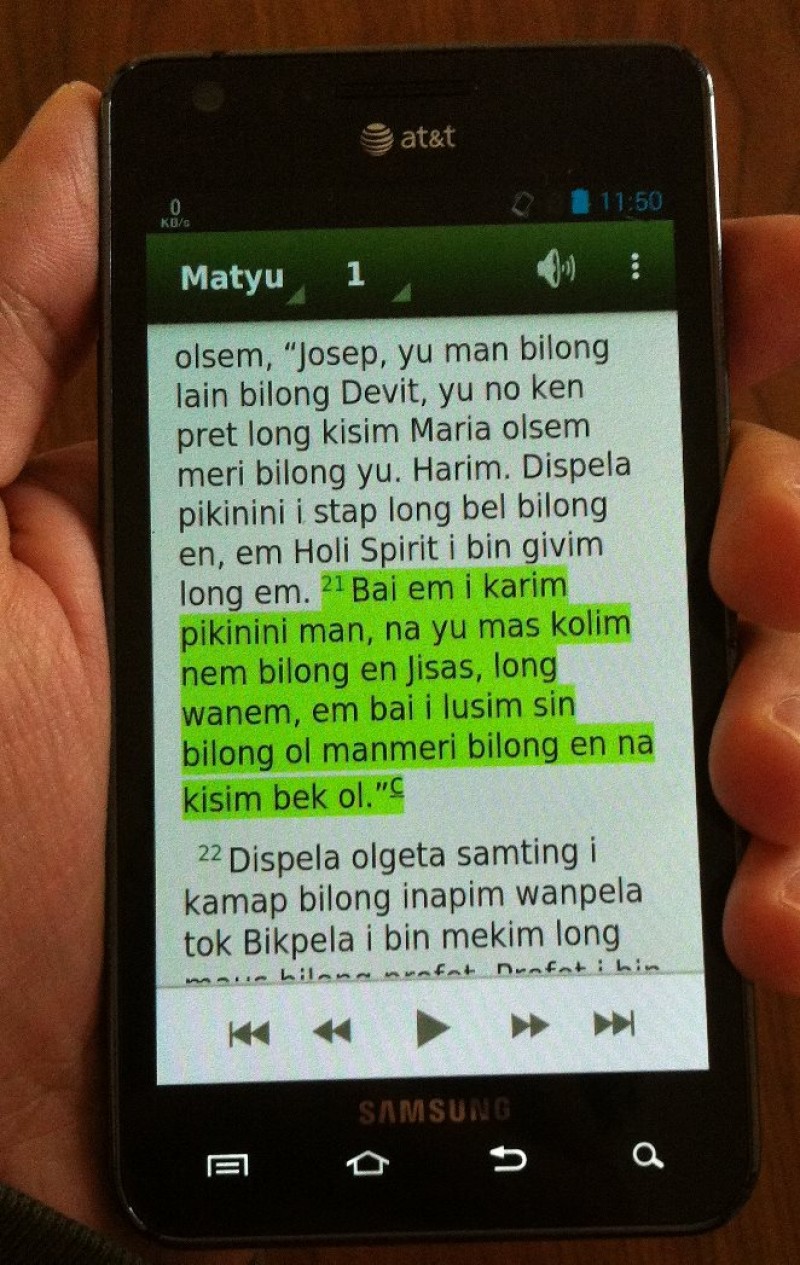

These devices offer many advantages: they are rugged, solar-powered, and simple to operate. However, they are more expensive than some people can afford, and their availability is limited. In recent years, the rise of the smartphone has offered a new way of distributing the translated scriptures that solves some of the drawbacks of the dedicated devices. By creating apps containing the text and audio recordings of the Bible, we give people the ability to access the translated scriptures for free on devices they already own and know how to use. The Scripture App Builder, a tool created by SIL, allows us to easily create apps for different languages.

Because they include the written text and audio together, these apps are also useful as literacy tools. As the audio recording plays, the app highlights each verse on the screen as it is read aloud. In this way, people can practice and improve their reading skills by following along with the recording.

In order to highlight each verse as it is read, the app needs to know the start and end timings of each verse in the recording. (For example, verse 1 starts at the beginning of the recording and lasts 4.3 seconds, verse 2 starts at 4.3 seconds and lasts 3.8 seconds, and so on.) By using speech-to-text technology, this can be done mostly automatically by using a computer to analyze the recording and text together. But sometimes the computer gets confused, so a human usually needs to listen and follow along with the results and manually correct the timings if the verses are not highlighted at the right time. The Scripture App Builder provides an interface for making these corrections.

Recently, someone here in Ukarumpa who is checking a new app for the Arop language asked me to make some tweaks to the Scripture App Builder to make it easier for him to modify the recording timings. Specifically, he wanted a way to be able to save his changes mid-chapter and load them back up later. I was able to fulfill his request, as well as add an auto-save feature so that his work would not be lost in case of a power outage. He was very appreciative of the changes I made, and for my part, I enjoyed being able to work on software that is more directly related to Bible translation.

Mumu

September 1, 2016

Most Sunday mornings, I attend a church in the nearby village of K'uina. One of the other missionary families who goes there recently returned to the U.S. for additional schooling, so the Papua New Guineans that live in K'uina organized a mumu to honor them and say goodbye. A mumu is a traditional method of cooking large quantities of food for celebrations in PNG. It involves digging a pit, filling it with hot coals or rocks, adding food, then burying the whole lot for hours so it can cook.

We didn't get to see the preparation (they woke up before dawn to get it all set up!), but we got to see them dig it all out again.

Yemli Trek

April 19, 2016

For 18 years, John and Amy Lindstrom and their family spent much of their time living in the remote village of Yemli in the Morobe province of Papua New Guinea. In 2010, the Malei language New Testament was dedicated. Thanks to the training the people of Yemli received as they helped work on the New Testament, they are now working on the Old Testament with John taking on a consulting role.

Recently, the Lindstroms invited the general population of Ukarumpa to join them on a good-bye trip to Yemli along with their son Samuel, who is about to graduate from high school and may not ever return to the village where he grew up. Since my software development work all happens in Ukarumpa, I eagerly accepted the opportunity to see another part of the country. There were 20 of us altogether. To get to Yemli from Ukarumpa, first you take

A 5-hour bus ride to the coastal city of Lae...

Then an hour boat ride south along the coast...

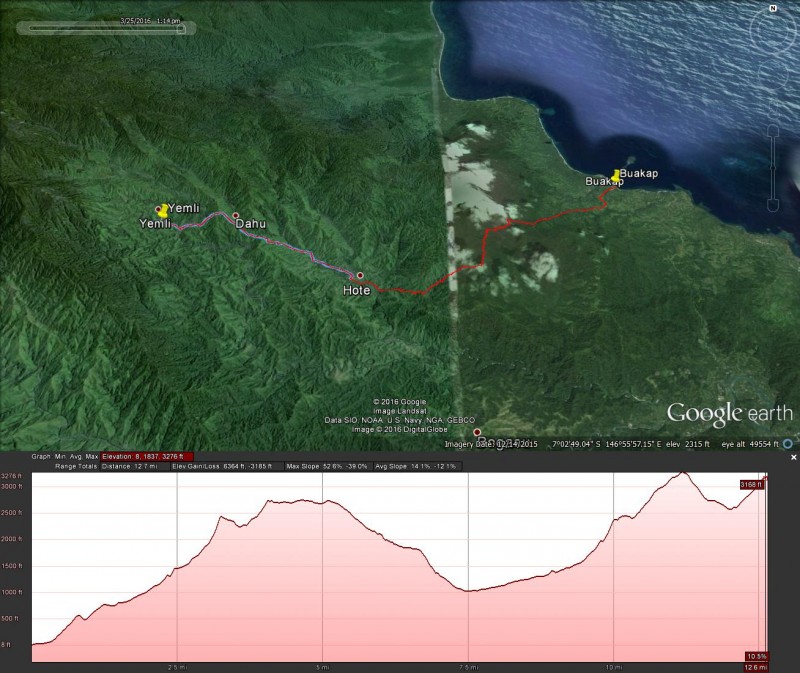

To the village of Buakap, where the hike begins. (There's no road!) The hike itself is about 13 miles though beautiful jungle/mountain country. While the mountains are very pretty to look at, they also make the hiking much slower and more difficult, especially while carrying all your clothes and sleeping bag and mosquito net. On the way to Yemli, we climbed over a mile up (6400 feet) and over half a mile down (3200 feet). We spent about 10-12 hours walking spread over two days to get there, sleeping at a school in the village of Hote overnight.

The trail took us up mountains...

Through jungles...

Across bridges...

And through rivers.

We spent two nights in Yemli itself. They honored our visit, and Samuel's departure, by giving us a traditional welcome (with singing and dancing), and killing and cooking a pig for us (which is a big deal in PNG culture).

On Easter Sunday morning, we attended the Yemli church service, then began the long walk back to the coast.

Here's some stats of the hike gathered and summarized by Chad Michael:

Wasfamili

December 8, 2015

As part of our language and culture learning here at POC, all of us students were paired up with a wasfamili (host family) from one of the villages in the area. We got together with our families several times over the course of POC, in situations that continued to stretch us as we grew more comfortable with the language.

The first visit, all the families came to the POC campus to eat dinner with us. After they arrived and we were introduced, each group sat down on a mat to eat (as is normal here), and the food was brought out to us from the kitchen. Then we learned a bit more about PNG culture as we observed and tried to discover answers to questions like, Who serves the food? Who gets served first? Are you supposed to start eating right away or wait till everyone is served? After the meal, we had some time to story with our family. I didn't know enough Tok Pisin at that point to say much of anything yet, so most of the storying consisted of waspapa talking and us doing our best to understand what he was saying and asking him to repeat stuff.

The following week, we had dinner with the families again, but this time at their houses. My wasfamili lives in the village of Guntabag, about a 15-minute walk from POC. In the weeks following the second visit, we returned to their house twice more, but this time to stay overnight in addition to eating dinner. Each visit, our Tok Pisin improved a little more. These visits also gave us our first taste of what PNG village life is like, and what it's like to eat and sleep in a bush house. All this, in turn, helped prepare us for the 30-day village living portion of POC (from which I just returned). More on that next time, with lots of photos.

And, for good measure, a couple moments that stand out in my memory:

I remember sitting on the mat at their house one night after dinner as my waspapa, Ninto, read from the Tok Pisin bible and then prayed. As he prayed, I was struck by the thought that, though I had to concentrate and struggle in order to understand what he was saying, God heard and understood his prayer just as easily as he understands my English ones.

Shortly before we all left for village living, all the wasfamilis came back to POC one last time for dinner and farewells. As we were saying good-bye, waspapa told us that, though we may not meet again on earth, we'll see each other again in heaven. Though I've heard many Christians in America say the same sort of thing, hearing it said in another language by someone from halfway around the world made me stop and realize that all followers of Christ, no matter where we're from or what language we speak, share the same hope of eternal life. So when we get to heaven, look me up - I'll introduce you to my wasfamili!

Village Living

November 29, 2015

After eight weeks of learning about language, culture, cooking, medicine, and much more at the main Pacific Orientation Course facility, the time had come to begin the final part of the course: four weeks living in a village, immersed in PNG culture.

The three single guys at this POC (Steve, Tony, and I) were assigned to the village of Bunu, a little more than an hour's drive north of Nobonob (the mountain on which POC is located).

The three of us had a wasfamili (host family) that looked out for us, took us places, introduced us to people, and taught us a lot about how to live in the village. They even built the house we lived in!

Being located right on a major road makes Bunu a somewhat atypical PNG village. Most people in PNG live by working in their gardens all day, hopefully bringing enough home for their family, and selling anything extra at the market. But the Bunu economy is powered by cash crops: cocoa, coconuts, and buai (or betelnut, which, when chewed with lime, acts as a stimulant. It's wildly popular in PNG culture.). They grow and sell these products, and use the money to buy their food. They also operate a roadside market, where they sell crackers, cookies, mangoes, and buai to passers-by. It's called Slowdown Market since it's right by a section of the road where the pavement is missing so all the cars have to slow way down.

Bunu is right on the ocean, which has its perks. The beach, though not sandy, was a popular hangout spot where we got to relax and talk with people. Seafood was plentiful, and we got to watch one of our brothers go spear fishing at night. My favorite was when he shot an octopus. First they kill it by turning its head inside out, then they take the body and slam it against some rocks for a while to tenderize the meat. Then wasmama fried it up and gave us some. It was quite delicious, very salty, very chewy, but didn't taste like seafood at all.

Simply surviving takes much more time in the village than in the US. To cook, you must first start a fire. Going to the store or market can take all morning: you wait by the road until a PMV (public motor vehicle) arrives. PMVs are cheap transportation, generally big vans with seats, and are nearly always completely full. So you might wait over an hour before one finally comes by that has space for you. (I forgot to take a picture of a PMV unfortunately.)

To get washing water, we (fortunately!) had a well right next to our house. Drinking water, on the other hand, was much harder to get because of the recent drought here. It got so bad that the government instituted a free truck that drives up and down the road, bringing people to a dam to fill up their containers with fresh water. Getting water is a multi-hour affair: you must first wait for the water truck to drive past, which was announced by all the kids yelling "wara wara wara!" as they dash through the village. Then you grab your containers, go to the road, wait for the truck to come back, and hope it's not full. If it's not, you join the dozens of Papua New Guineans already on the back of the flatbed and take the bumpy ride to the dam. The truck drives away to get more people as you all fill up your containers and wait for the truck to come back and take you home. Sure makes me appreciate unlimited, clean water available inside your house at the turn of a knob!

We spent lots of time storying with our wasfamili and other people from the village. Our conversation topics varied wildly, these are just a few: how to get to PNG from America, the PNG education system, how to avoid shark attacks, movies, English, magic, Obama, what American houses are made of, World War II, animals of PNG, the Chicago Bulls, and much more. They were also very interested in our thoughts about Christianity. The area surrounding Bunu is primarily Catholic, but a few other groups (especially the SDA) are growing stronger here, and several people wanted our opinion on certain doctrinal issues and passages that the Catholics and SDAs disagree upon. I had a Tok Pisin New Testament with me (I left it in the village when we left), and we were able to look up passages together, emphasizing that the Bible is the ultimate authority.

Other highlights from village living include visiting the haus sik (hospital) to get a malaria test (I didn't have malaria, but it sure felt like I did!), helping a guy named Erico build a fence around his garden...

visiting a whole bunch of World War II relics...

and playing in a mambu (bamboo) band.

(Turn up your volume, the audio turned out rather quiet!)

As is part of the culture, there was a big farewell celebration for us at the end of our time in the village. We and many others contributed food for the women to cook, including a chicken that we watched waspapa kill and clean. (We wanted him to kill one of the chickens that liked to sit under our house and cluck all night, but those weren't good for eating apparently.) They also dressed us up in traditional ceremonial clothes which included, among other things, dogs' teeth and pigs' tusks and bird of paradise feathers. We even attended a morning church service while dressed up, which caused quite a stir among the congregation as the priest (who is from Poland) tried very hard to conceal his surprise and amusement at our unexpected appearance.

Now that my village living time is over, I'm thankful for the relationships I formed there, for the chance to improve my Tok Pisin, and also for the greater appreciation I gained for what daily life is like for the average Papua New Guinean. As I live here day after day in my house in Ukarumpa with screened windows, running water, an indoor bathroom, a refrigerator and stove, and a comfortable bed, it's easy to forget how much easier I have it than most of the rest of the people who live in PNG. My month in the village has made me realize more than ever how much God has given me, for which I am most thankful.

Tok Pisin

October 23, 2015

Disclaimer: I am neither a linguist nor a native Tok Pisin speaker. Proceed with caution.

This post contains a very brief description of the language itself as well as a few of my favorite words and phrases. Another post describing how we go about learning Tok Pisin at POC can be found here.

I never really enjoyed learning Spanish in high school, so it comes as a pleasant surprise to me that I'm actually having fun learning Tok Pisin. Partly it's because it's because I'm surrounded by a bunch of speakers of the language to practice with, but also because it's reasonably easy to learn if you already speak English. A lot of the vocabulary is similar to English (usually spelled differently, but always phonetically.) Verbs are dead simple - they only have one form, unchanged by tense or subject. (Tense is indicated by context and a few helper words. So while this makes it easier to speak, it does mean you need to pay closer attention to find out if someone has done, is doing, or will do something.)

The language also has far, far fewer words than English, so there's not nearly as much vocabulary memorization needed. So, since there is no Tok Pisin word for "pulpit", you say something like bokis bilong pasta autim tok bilong God ("box in which the pastor speaks the words of God"). "Esophagus" becomes rop bilong kaikai go daun ("rope that food goes down"). "Earthworm" becomes snek bilong graun ("snake of the ground"). And so on.

There are also fun words that were formed by combining multiple English words. For example:

kesmasis (from "case matches") - a lighter

hangamapim - (from "hang up") - to hang something

bonara (from "bow and arrow") - but actually, a bonara is just the bow. The arrow is called a spia (spear).

And then there's expressions. If you want someone to raise their voice, you ask them to apim nek (up their neck). The liklik haus (little house) is the bathroom. The emotional center is the belly, not the heart, so to encourage someone, you strongim bel (strengthen the belly). If you are angry, you have belhat (hot belly). And if you are convicted by someone's words, the speaker has sutim bel (shot your belly). However, if you gat bel (have a belly), you're pregnant. And my personal favorites so far: namba 7 (number 7) is a hand axe, because a hand axe is the same shape as the number 7. And namba 11 is, of course, a runny nose.

Kisim Save Long Tok Pisin Long POC

October 23, 2015

("Learning Tok Pisin at POC")

God i gat wanpela Pikinini tasol i stap. Tasol God i laikim tumas olgeta manmeri bilong graun, olsem na em i givim dispela wanpela Pikinini long ol. Em i mekim olsem bilong olgeta manmeri i bilip long em ol i no ken lus. Nogat. Bai ol i kisim laip i stap gut oltaim oltaim.Jon 3:16 (Buk Baibel long Tok Pisin)

Papua New Guinea is home to over 800 languages, so the people of these language groups need a common language to communicate with each other. Some use English, but the language of choice in most of the country is Tok Pisin. If you speak English, you're well on your way to learning Tok Pisin, though there's still a respectable amount of work to do before you can really understand, and then speak, it. And, since speaking the same language apparently makes it easier to build relationships with people (who knew?), a major component of POC is learning Tok Pisin. Our learning takes place in three ways: large group learning, small group discussion, and conversations with the Papua New Guineans around us.

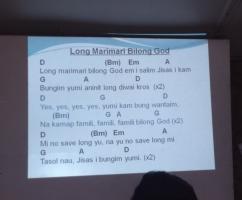

In our large group sessions, we've had a few lectures on Tok Pisin grammar. We also read through the book of Jonah aloud to practice our pronunciation (especially the vowels) and sang a number of Tok Pisin songs.

But most of our structured learning takes place in our Tok Pisin small groups. Each group is made of about six students and is led by a Papua New Guinean tisa (teacher). My group's leader is Tisa Mat. We spend many sessions doing various activities to help build our vocabulary and intuition of how the grammar works, including simple conversations, listening to and telling stories, and games like I Spy and 20 Questions.

Besides these sit-down-and-talk activities, the small groups have also watched people make things to give us practice asking questions. (What are you making? What is it used for? etc.) We've also gone with our teachers to see and discuss a garden, and a house under construction. So in addition to improving our language, we also get to learn more about Papua New Guinean culture and daily life at the same time.

I also got a very small taste of linguistics. One of our assignments was to record and transcribe a story told by our teacher. I actually thought it was a lot of fun; I wouldn't mind learning more about linguistics if I ever end up working on translation software someday.

Here's a transcribed snippet of Tisa Mat's story about pig hunting. The first line is what I heard him say in Tok Pisin, the second line is translated into English as literally as possible, and the third line is my "free translation" of how you might say it in English.

Mi bihainim lek mak bilong ol. Mi no gat dok. Mi karim gan.

I follow leg mark of them. I no have dog. I carry gun.

I followed their footprints. I had no dog; I carried a gun.

The third learning method, conversations with Papua New Guineans in the area, I'll leave till next time when I'll talk about my wasfamili. (See what I did there? I used a Tok Pisin word without defining it, leaving you wondering what it could possibly mean. You will now spend the next several days glued to your computer, madly refreshing png.bgreco.net, waiting for that glorious hour when I finally click "publish".)

Welcome to POC

October 16, 2015

Ah, the Pacific Orientation Course. Before I arrived, I wondered what could possibly occupy my time for three solid months here. The answer, as I quickly found, is "quite a lot". Here's the summary, more will follow later. (I have 3 more half-written posts at the moment that will probably show up on here before too long.)

POC, as its name implies, is a training course designed to prepare missionaries for life in the Pacific area. There are 27 adults and almost as many kids attending my session. Once we are finished here, many will stay in PNG, and others will go to Australia, Indonesia, and Vanuatu. We spend the first eight weeks here at the POC campus, then scatter to various villages in this region to complete the four-week village living phase of the course.

The city of Madang is located on the north coast of Papua New Guinea, 5 degrees south of the equator. The POC campus is located at the top of one of many small mountains near Madang. We're 1000 feet up with a beautiful view of the ocean and surrounding country. The immediate area surrounding POC is known as Nobonob, a collection of villages that share a common tokples ("talk place", or local language). The Nobonob New Testament was completed several years ago, and the Old Testament is currently in progress. I still find it incredible that the people who live on the next mountain over, a three-hour hike from here, speak a completely different language!

Here's what a typical (if there is such a thing) weekday here looks like:

7:00 - Breakfast

8:00 - Bible time

8:15 - Tok Pisin (language) large/small groups or other lecture

10:00 - Tea

10:30 - Class time

12:15 - Lunch

1:00 - Rest

2:00 - Swim or hike or class time

5:45 - Dinner

Sights from around POC:

On the weekends, we've gone to a few churches in the area so far:

We've also driven down to the ocean a few times for swimming/snorkeling, which is a great way to relax, cool off, and see a bunch of neat-looking coral and fish whose names I do not know. Also on the weekends, we are responsible for cooking our own food over a campfire in preparation for village living. Not only does the weekend cooking teach us what sorts of things you can make with the food available for purchase here, but it also gives us a better understanding of how people here live their daily lives. I've certainly gained an appreciation for those magical devices found in kitchens back home that allow you to instantly conjure a steady flame of any size you want just by turning a knob!